THE FASHION FOR ZAKOPANE: SELLING A MYTH

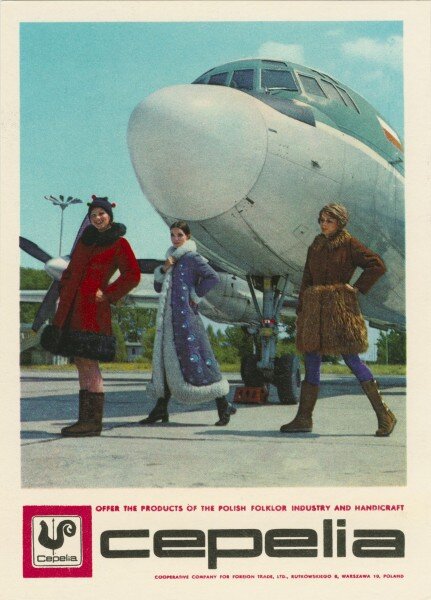

Poster advertising the confectionery of "Cepelia", 1970s, private collection

Zakopane is a small town in the Tatras. Its fame is due to its charming location among the mountain peaks, but also to the careful marketing of Tytus Chałubiński, a physician who at the beginning of the 20th century promoted Zakopane as a mecca for tuberculosis patients, launching the construction of sanatoria, which until the war sprouted there like mushrooms. Zakopane was supposed to treat pulmonary diseases, even if the fickle climate and howling wind did not seem encouraging. And even if, as one Zakopane native claimed, the air there would send the healthy to their beds and turn strong men into alcoholics.

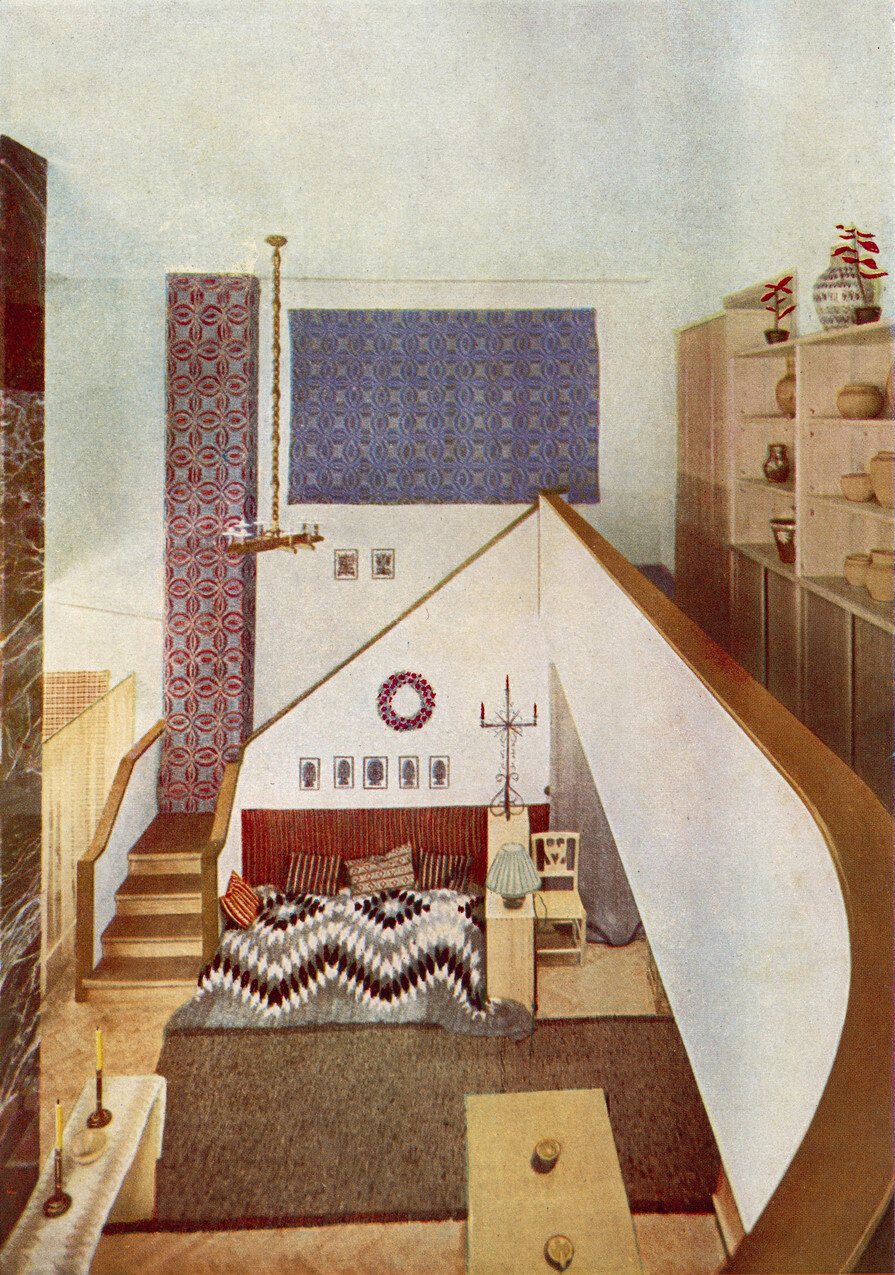

The interior of the "Village Artistic Handicraft" shop, designed by Czesław Knothe, 1935, [in: "Arkady" 1936 No. 1, p. 18

During the twenty years between the wars, the capital of the Tatras pulsed with life. It was said to be the centre of the known world, where trains reached the end of the route. Zakopane drew not only consumptives but also artists and writers, and they were followed by the cream of pre-war Polish society. It was then that incredible stories and legends began to grow up around Zakopane, artworks and buildings inspired by the mountain air and mountaineers’ crafts. The Zakopane style arose, created by Stanisław Witkiewicz, an architect who settled in Zakopane in 1890 and drew on experiences from his studies in Munich and a fascination with wooden architecture to forge his dream: a fictional folk style that sparked not only the colonization of the mountaineers but also their progressive self-transformation into figures of folklore. In other words, a myth arose. And the myth quickly began to be sold.

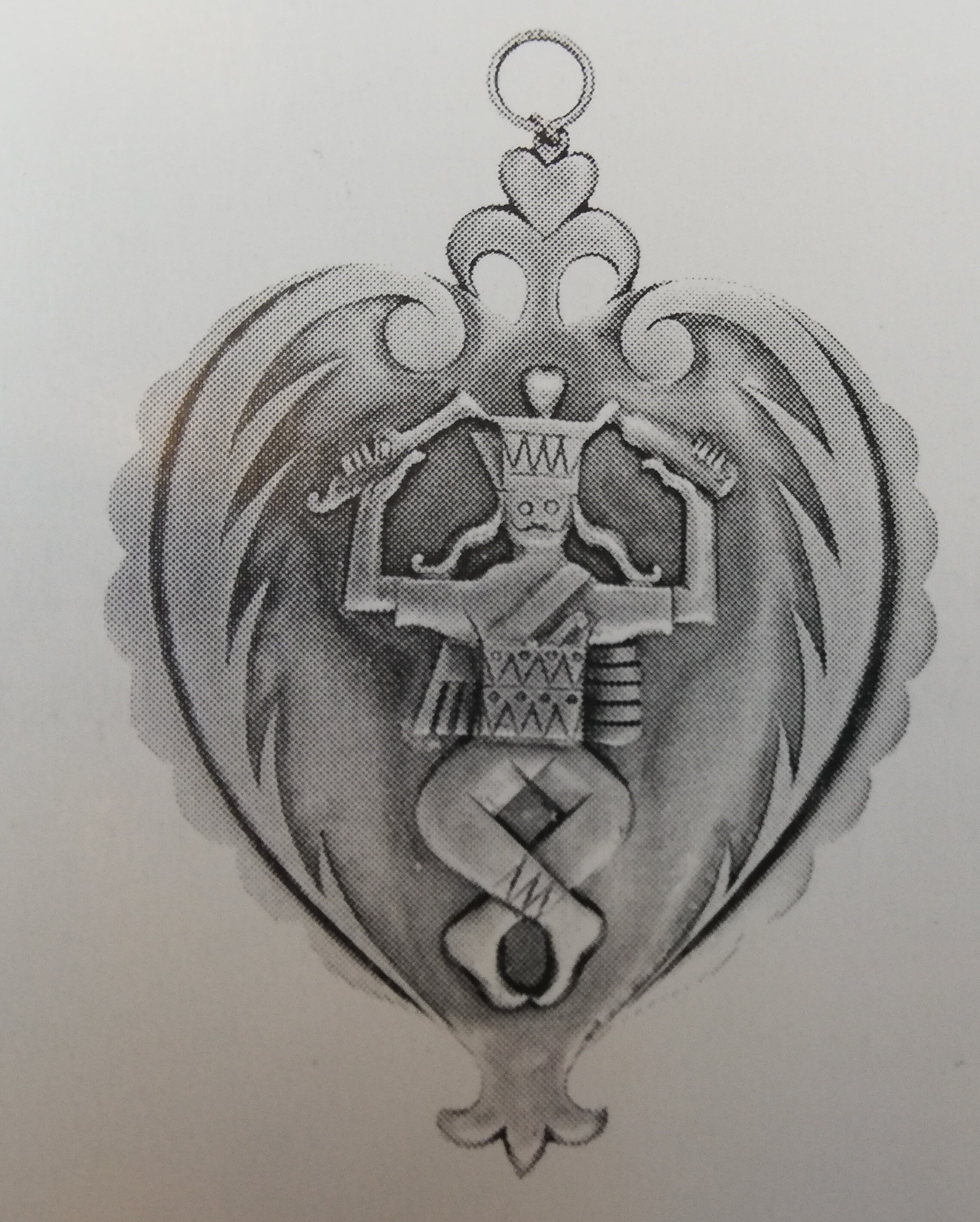

Silver pendant "Janosik", 1948, Institute of Industrial Design

The fortunes of Zakopane and folk style appear to be ambiguously joined. The fashion for folklore begun in a quest for a national style was one of the reasons for the popularity of Zakopane in the 1920s. In turn, the atmosphere of the town and the legend associated with it not only shaped the folk culture created far from the bucolic Podhale, but seemed to intensify it.

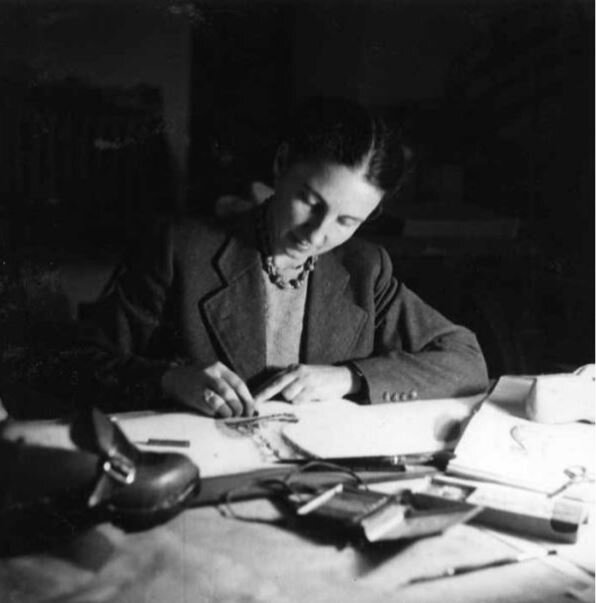

Krystyna Tołłoczko-Różyska, Zakopane of the 1940s, photo from the resources of the National Archives in Krakow

Zakopane was not interested in fashion, with a few exceptions, such as the designs by Maria “Dziunia” Witkiewicz, who combined Zakopane patterns, including the traditional parzenica, with French-style cuts fashionable at the time. (Dziunia is pictured with her cousin Witkacy, son of Stanisław Witkiewicz—artist, writer, and the most colourful figure in Zakopane.) Nonetheless, particularly in the 1930s, elegant women from Warsaw brought sheepskin coats, jerkins, and embroidered blouses home from Zakopane. They wore red bead necklaces, mountaineer boots, and embossed belts, which they combined with long skirts and bouffant blouses. Alongside other folk items, Zakopane ornament became a part of the fashion of the day, which the press proudly advised should be exhibited abroad. In 1939, in connection with the skiing championships of the International Ski Federation (FIS), a whole series of sports outfits were created featuring Zakopane embroidery, and later presented at a special fashion show.

Maria Witkiewicz ("Dziunia") and her cousin Stanisław Igancy Witkiewicz (Witkacy) in costumes according to her design, Zakopane in the 20's of the 20th century, photo from the collection of the Tatra Museum of Dr. Titus Chałubiński in Zakopane.

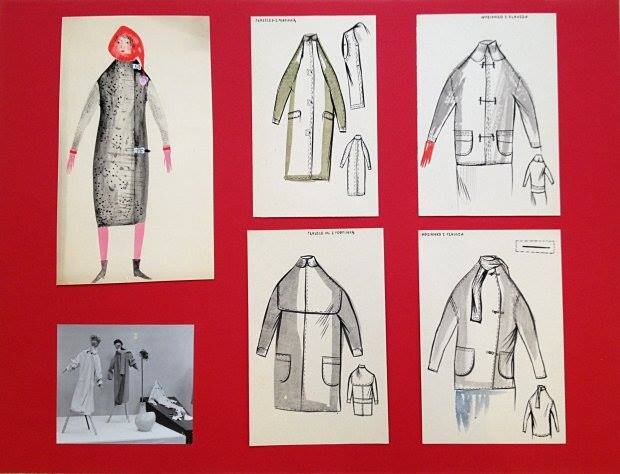

Barbara Gawdzik-Brzozowska, coat designs, 1950s, courtesy of the artist's family

After the Second World War Zakopane did not lose its importance, although most visitors would be simply tourists. The legend of the town was quickly reduced to product, as was folk culture in general, which for the communist authorities had a value that was not only national but was primarily connected with the strongly hybrid tradition of the social class of peasants and industrial workers. Traditional Polish folklore was promoted everywhere, from the magazine Nowa Wieś, which was intended to promote a modern lifestyle in rural areas, to the fashion magazines Moda i Życie and Świat Mody, where traditional folk costumes were featured alongside trends borrowed from France but adjusted to the possibilities of a shortage-driven market. In Zakopane itself, fashion was of interest mainly at the Helena Modrzejewska Lacemaking School, which under the direction of Maria Bujakowa was completely reformed, introducing a breeze of modernity to a musty institution. Bujakowa herself wrote of lace that it required a thorough re-evaluation, a reversal of the existing patterns, and a fresh start. Although kilims took precedence at the school, the clothing designed by the pupils with lace elements conveyed a new value; they were simpler, functional, and first and foremost fashionable.

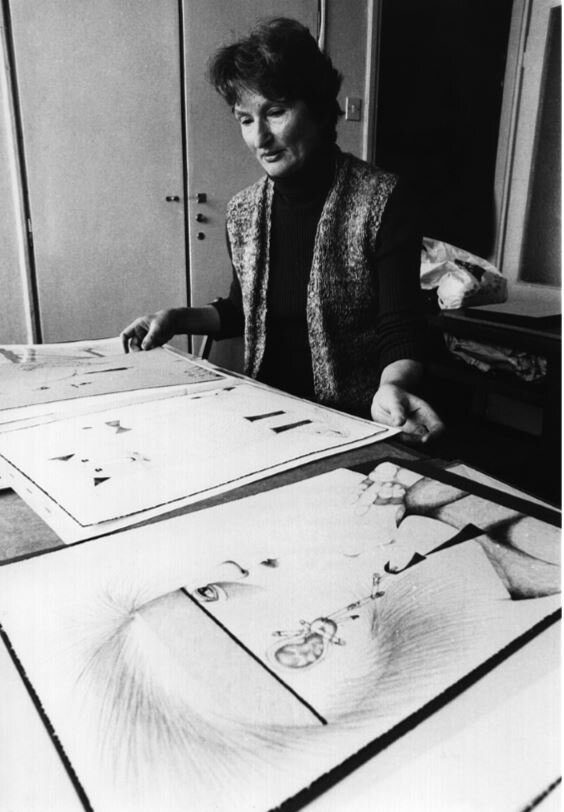

Barbara Gawdzik-Brozowska at work, 70's, photo: Stanisław Momot, courtesy of the artist's family

A similar view of the weight of Zakopane history was taken by Krystyna Tołłoczko-Różyska, a well-known architect who settled in Zakopane in the late 1940s and designed jewellery with her husband, Józef Różyski. And it was in jewellery that Zakopane patterns first appeared, in the form of the Harnasie bandits but also stylized ornaments, running somewhat counter to social realism. But unlike other designers, including Henryk Grunwald, who was famed for his fairly superficial treatment of folk patterns, Tołłoczko and Różyski identified the Zakopane style first and foremost with the simplicity and rawness of the materials. In Zakopane they founded a model cooperative where they trained pupils from the Kenar art school, producing necklaces, beads, and pendants from natural materials—wood and wood derivatives (bark, branches, roots). This gave rise to “poor jewellery,” inexpensive and avant-garde in form. Tołłoczko was also interested in fashion. She designed, and often also sewed herself, clothing, shoes and bags, using linen, felt, leather and wool. All surprisingly simple for the time, practically minimalist. The traces of this unconventional thinking were also reflected in her architectural designs and in an article from 1955 which Tołłoczko wrote with Anna Górska for the magazine Architektura. She saw opportunities for Podhale primarily in new artistic expression, a neo-Zakopane style combining contemporary form and functionality with the rich tradition of the region.

Zakopane Model Workshops, 1970s, photo: Stanisław Momot, Central Photographic Agency (KAW-CAF)

Barbara Gawdzik Brzozowska, unrealized mural design for the Sport Tourist office in Zakopane, circa 1963, courtesy of the artist's family

Barbara Gawdzik-Brzozowska pursued a similar thinking at this time. This painter and illustrator was one of the founders, along with Władysław Hasior and Antoni Rząsa, of the grass-roots Galeria Pegaz, which aimed at rescuing Zakopane from the threat of provincialism and a misguided sense of traditionalism. Gawdzik implemented the postulates of Pegaz not only in urban space, by designing mosaics and murals for example to mark the FIS ski competitions, but also in fashion. The clothes she designed were striking for the simplicity of their composition and geometrical forms, and an animated treatment of details, often accentuated by strong colour. The drawings were painted with a subtle, elegant line, with irony but also anecdotal to a degree, stressing lightness in motion and betraying a certain playfulness. Gawdzik used to say that there was nothing more beautiful than young girls, and that she would try to dress women who were young in spirit.

Folk and modern, [in:] "Nowa Wieś", No. 7 (835), 1961

Customers see Barbara Hoff dresses on mannequins in Cedet, 1967, National Digital Archives

All of these Zakopane initiatives, which drew from folk culture with a certain distance but not without historical reflection, were eventually absorbed by Cepelia, the state union of craft cooperatives established in the late 1940s, whose shops enjoyed undying success throughout the Polish People’s Republic and whose products became a major export good of communist Poland. The Zakopane Pattern Workshop, belonging to Cepelia, typically produced short and thus exclusive runs of clothing. Initially the patterns were supplied by local designers, but in time, when in the early 1960s folk culture began to interest such institutions as the Institute of Industrial Design, the Moda Polska enterprise and the Cora clothing plants, and fashion became the highlight of the annual Cepeliad shows, individual initiatives were driven out by designs produced centrally in Warsaw, offering pseudo-mountaineer inspirations in place of a modern-spirited folk outlook. These were mostly superficial pastiches of folklore motifs, often from differing regions and handcraft traditions, in fashions transplanted from the West. The Zakopane style was transformed into another fiction, and Zakopane was once again sold, so that finally, at the threshold of the transformation from communism, it could live out its days in the form of tawdry commercialism.

Maria Wąsowicz-Sopocka, Bride from Bukowina Tatarzańska, [in:] "Świat fashion" No. 36, 1958

![Folk and modern, [in:] "Nowa Wieś", No. 7 (835), 1961](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56995a70fd5d08aedf1bf6da/1578930893392-IWDXGFUAYCY4KBNW4NHT/9..jpg)

![Maria Wąsowicz-Sopocka, Bride from Bukowina Tatarzańska, [in:] "Świat fashion" No. 36, 1958](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56995a70fd5d08aedf1bf6da/1578930969378-FM3WDYVEPGLW4USGKUUG/13..jpg)