Aga Prus Warsaw Shoemakers

“CONTINUATION OF MY GRANDFATHER'S WORK IS MY CONNECTION WITH THE WORLD THAT NO LONGER EXISTS.” AGA PRUS, A GRANDDAUGHTER OF POLISH LEGENDARY CORDWAINER PUTTING A MODERN TWIST ON TRADITIONAL SHOEMAKING

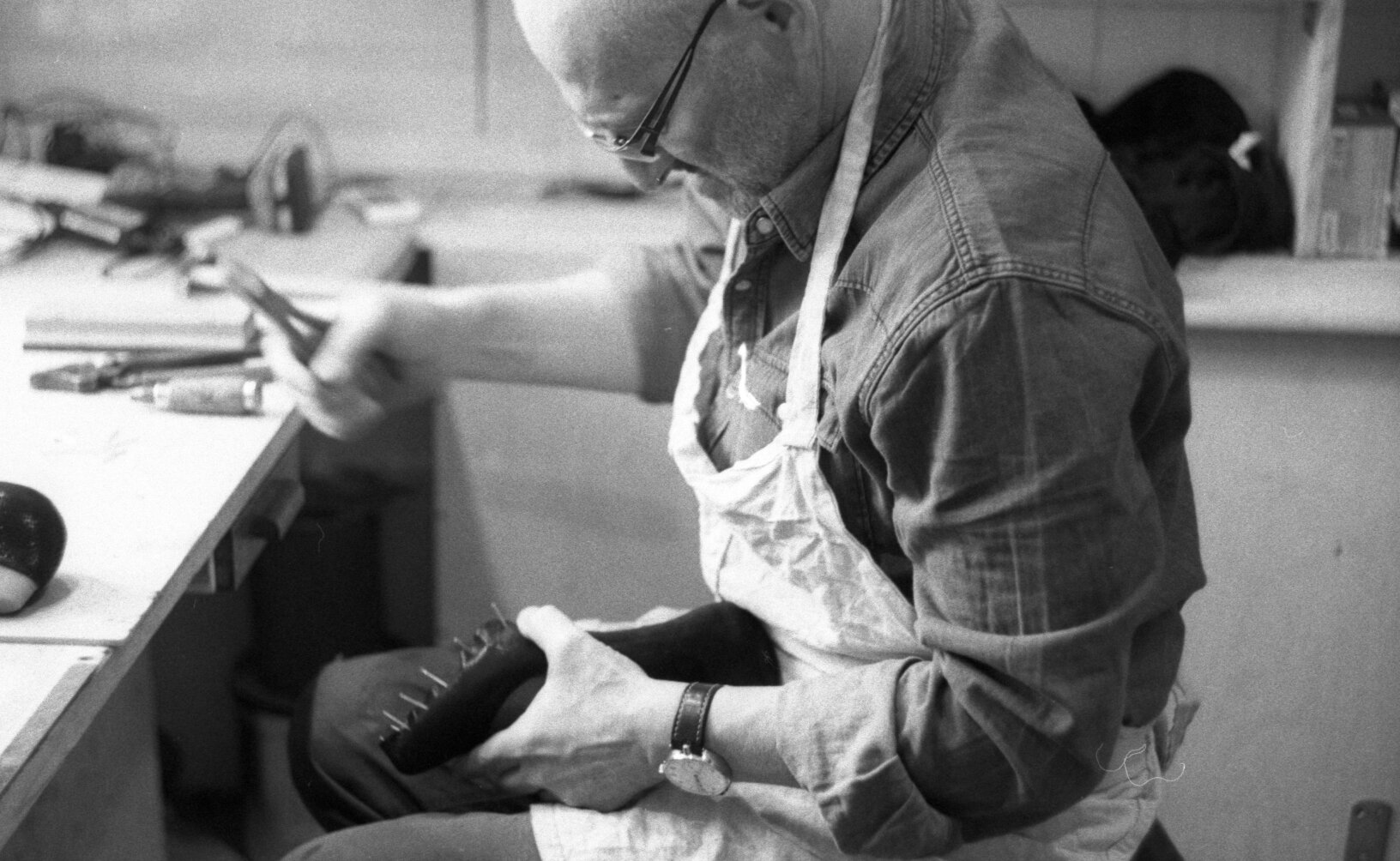

Janusz Prus (master), Aga Prus (designer) and Zbigniew Gadomski (shoemaker), photo by T. Pasternak

When people think of handcrafted shoes, they naturally think of UK, Italy, Portugal… however Poland has a long history of shoemaking. During interwar years, Warsaw counted over 2000 shoemaker workshops which have been a substantial part of the Polish economy. While nowadays it is an endangered sector, it certainly is not extinct. There are many handmade shoe enterprises in Poland providing craftsmanship at an exquisite level and competitive price. Rising urgency to divert fashion system towards a more sustainable route made many businesses reassess and change their schemes of work. What many businesses have to learn and adapt to, a naturally sustainable bespoke sector has running in their veins since generations.

One of the exciting places for traditional craft connoisseurs is Aga Prus Warsaw Shoemakers located in Warsaw’s district of Ochota. It is a place honouring tradition and longevity, where shoes are made from the initial concept till the final wearable piece by a small team of highly skilled craftsmen. Such shoes last and age with grace. Aga Prus, its founder and designer continues the craft born in her grandfather’s hands almost a hundred years back. His legend inspires and motivates her and his craft marks the level of excellence she strives for in her own practice.

Tadeusz Mizerski and Brunon Kamiński (on the right) at work, Nowy Świat, Warsaw, 1982

Brunon Kamiński, is a name well known in Poland associated with the finest of Polish shoemaking. His story is one of going from the rags to the riches. From a small village boy to successful footwear entrepreneur, whose designs graced the icons of the cinema and key personas from the politics. Born in a small village in Pomerania, a region in Poland’s up north, he dreamt of becoming a shoemaker since childhood. It was not a popular craft locally where he grew up. People in the countryside spent most of their time bare-feet. Shoes, though, have always been a signifier of economic status; to many were a synonym of wealth. Young and determined Brunon moved to Gdynia aged 12 to seek his fortune and pursue craft education. Soon enough, he realised he needs to move to Warsaw to learn from the very best in the industry. Insatiably curious and keen to learn the secrets of the discipline, he managed to apprentice at 13 masters still before the eruption of the World War II. In 1943 he opened his own Artistic Shoes Atelier, which later closed during the Warsaw’s Uprising.

Post-war period put a lot of businesses in a doldrum with material shortages and heavy taxes. To persevere this economic crisis, Brunon secured a position at the theatre where he got to run a footwear workshop. The time there awakened his passion for historical shoes, old techniques and leather treatments. In result of that, later Brunon would realise replicas of shoes for museums. After two years Brunon reopened his business at the Nowy Swiat 22, an address neighbouring to his former studio which haven’t survived the war. The shop’s popularity picked up quickly, and his shoes soon graced the feet of celebrities, actresses as well as party dignitaries, and their wives. The Leather Craft Guild appointed him to make a pair of shoes for Pope John Paul II. This commission was an absolute white-glove service realised in uneasy material to work with - white nubuck. Brunon enjoyed letting his imagination fly high creating whimsical designs and pushing boundaries of traditional shoemaking. Taking part in two editions of the World Footwear Exhibition in Munich, further demonstrated his position among the top shoemakers globally. His playful designs, “the plane” and "the orchid”, won silver and gold medals and allure to this day. Brunon also made horse riding shoes and took up a challenge to create the lightest pair of jockeys in Poland; he successfully designed shoes that weighed only 28 grams. The 60s brought him a collaboration with Polish fashion house Moda Polska. Brunon’s designs perfectly complemented collections from Jadwiga Grabowska. Later Xymena Zaniewska commissioned him to design shoes for tv announcers.

Brunon passed away in 1993. His work weathered war and challenging post-war times. Knowledge he managed to pass on still resonates through the work of his students today. One of them - his nephew Jacek Kamiński continues to run his Artistic Shoes Atelier under the same address. However, Brunon would be perhaps even more surprised that his granddaughter will eventually pick up the craft too.

Having a family rooted in traditional shoemaking Aga grew up surrounded by craftsmen. “We used to spend Saturdays at grandparents’ at Nowy Swiat. Me, sister and mum went upstairs while men were working downstairs in the workshop”. She admits, she initially looked at the craft as an occupation assigned to men. Since childhood Aga enjoyed painting but was equally drawn to maths as well. Hence, the architecture degree seemed to her like a right choice. Pivoting point came after graduation upon securing a job at a graphic design studio. She understood that work in the office environment is just not for her. She realised how big treasure her family heritage craft is and decided to embark on a career in shoemaking. “Shoemaking is a difficult craft involving so many stages. Shoe though does not only have to look good but foremost be comfortable. It impacts our body posture, our spine..” Support of her father Janusz was priceless. Once the most talented apprentice of Brunon Kaminski, he had skills and years of experience. He studied wood technology, built windsurfing boards, run a production of ice skaters’ shoes using his very own designed technology. Janusz is a problem-solver unafraid to approach the most challenging wishes of a client "usually assertive, unless to customers”, adds Agnieszka.

There is no designer to direct the general aesthetic in the traditional formula of a shoemaker workshop; models are born from client inspirations, often copied from journals. Asked about design role in her grandfather’s workshop, she says “There was no one who only dealt with design. Craftsmen, shoemakers showed greater creativity. Also French magazines, pictures brought in by clients… They all informed and inspired designs displayed on the site.” Aga occasionally gets requests for “boots like Margiela’s”, but she never does such copies. Her studio stands at the intersection between a boutique, a contemporary footwear brand and a workshop relying on traditional approach to making. Clients can either pick one of the sample models from the website or come up with their own concept. Each design is completely unique. It represents both client’s personality and Aga’s design aesthetic, while balancing comfort and beauty.

As much her grandfather enjoyed extravagance and pushing boundaries of what can a shoe be, Aga admires the classics. Her designs seek to compliment the look rather than overwhelm it. She visibly nods to a traditional form and vintage styles from her grandfather’s era recapturing its mood and spirit. Aga takes particular pride in her heels, which are highly comfortable despite the height. Precise construction details, subtle stitching, flawless positioning of straps is where her architecture background is clearly visible.

Aga Prus’s brand grows slowly but steadily. Starting off with women’s collections, later adding men’s and lately also accessories to its offering. Women’s styles are her favourite to work with for there is more to experiment in shapes, colours and details. Men coming to her studio tend to be stricter in what they want and less open to unorthodox ideas. “Even though I do orbit around classics, women’s shoes give me more creative freedom(…) in men’s it is often better to keep simple and classic. Most of the time the less changes, the better. ” Asked about her typical customer she says “We have a niche - a large part of our orders are weddings, and most of our regular customers have unusual feet.(…) What all our customers have in common is individual approach to footwear. They treat it as investment for many years.”

"The shoe preparation process takes a long time. We invite the client to three approximately one hour meetings. Going through this process is a whole experience creating a special relationship with our clients.” The process takes between 7-12 weeks depending on the type of a shoe and whether additional fittings are required or not. “Each case is different and requires an individual approach. You have to have a lot of humility and openness. Schemes rarely work so you can't speed things up. (…)Model often evolves still during the try-on. It is a constant conversation. Together with the client we come to the final pattern and shape.”- explains Aga. Janusz prepares a prototype based on Aga’s sketch, which is later fitted on during the second meeting. Once both sides are happy with the outcome the shoe progresses to the clicking and closing stage. Leather pieces are cut and sewn together and the upper is constructed in its final shape. Finishing the shoe requires painstaking attention to detail and involves steps like merging upper and sole, hand stitching, dressing the leather which all take at least 7 working days per one pair. Such an artisan crafted pair gets a lifetime guarantee for future in-house repairs and adjustments. Shoes made in such intricate way are a unique form of expression of the wearer's identity.

Aga and Janusz Prus admit that the studio means to them more than just a business. Working with the craft and skills inherited from Brunon seems to them like a honourable duty. Craft is so rooted in their family that they could not just let it go. “Continuation of my grandfather's work is my connection with the world that no longer exists.” Sentimental about the spirit of a pre-war Warsaw, Aga finds Brunon’s shoes to be an essence of those times.

It can be arguable whether the craft is dying off or is in a long-run process of a slow revival. Aga Prus mentioned she worries about the continuity of shoemaking craft due to the lack of appropriate young apprentices. The system of apprenticeships is largely gone, while process of teaching a student is extremely time-consuming. It is something smaller studios simply can not afford. For such demanding, slow produced products like handcrafted shoes, time really is money. Nowadays with its aggressive competition and fast pace of the market, forms a very challenging environment for small craft enterprises to grow and develop. On the other hand we are witnessing a significant spike of interest in craft and artisan goods from the consumers’ side. Over the last couple of years and most visibly throughout the pandemic, it became clear that local businesses and small scale, demand-led manufacturing are the way to go.

Hopefully, it will go beyond just a new consumption trend and attract a lot more young people to learn the craft and consider it a promising career opportunity. Their fresh outlooks will usher new paths for craftsmanship to grow and adapt to a fast changing world and form new models to continue and utilise traditional craft in a contemporary way.

Check out Aga Prus’s website to see examples of her models and book your exclusive bespoke shoemakers experience for your next visit to Warsaw.

All images and video courtesy of Aga Prus