ANNA JANKIEWICZ - BURDA

HERITAGE WARDROBES AS ARCHIVES OF IDENTITY

“I always saw my mum as the woman that slept 4 hours a night, drank four coffees a day, lifted, moved,

and carried heavy things, never asking for anyone’s help, almost as a way to prove her strength

in every way she could. Physical body was only a tool for practical deeds, simply useful,

never a thing to be appreciated or noticed too much. And yet, amid all that hustle, she made sure that

whatever touched her skin was high-quality materials.

The closet she owned in the past turned into an archive I needed today.”

Anna Jankiewicz is a recent graduate of Central Saint Martins Graphic Communication Design BA. Her Polish upbringing strongly influenced her artistic perception. She’s fascinated by how Eastern European culture clashes with the West. Within her practice she focuses on women’s stories drawing from gender studies, feminism and appreciation for women’s experiences in today's society. Anna communicates through visual language sitting between photojournalism and art filmmaking.

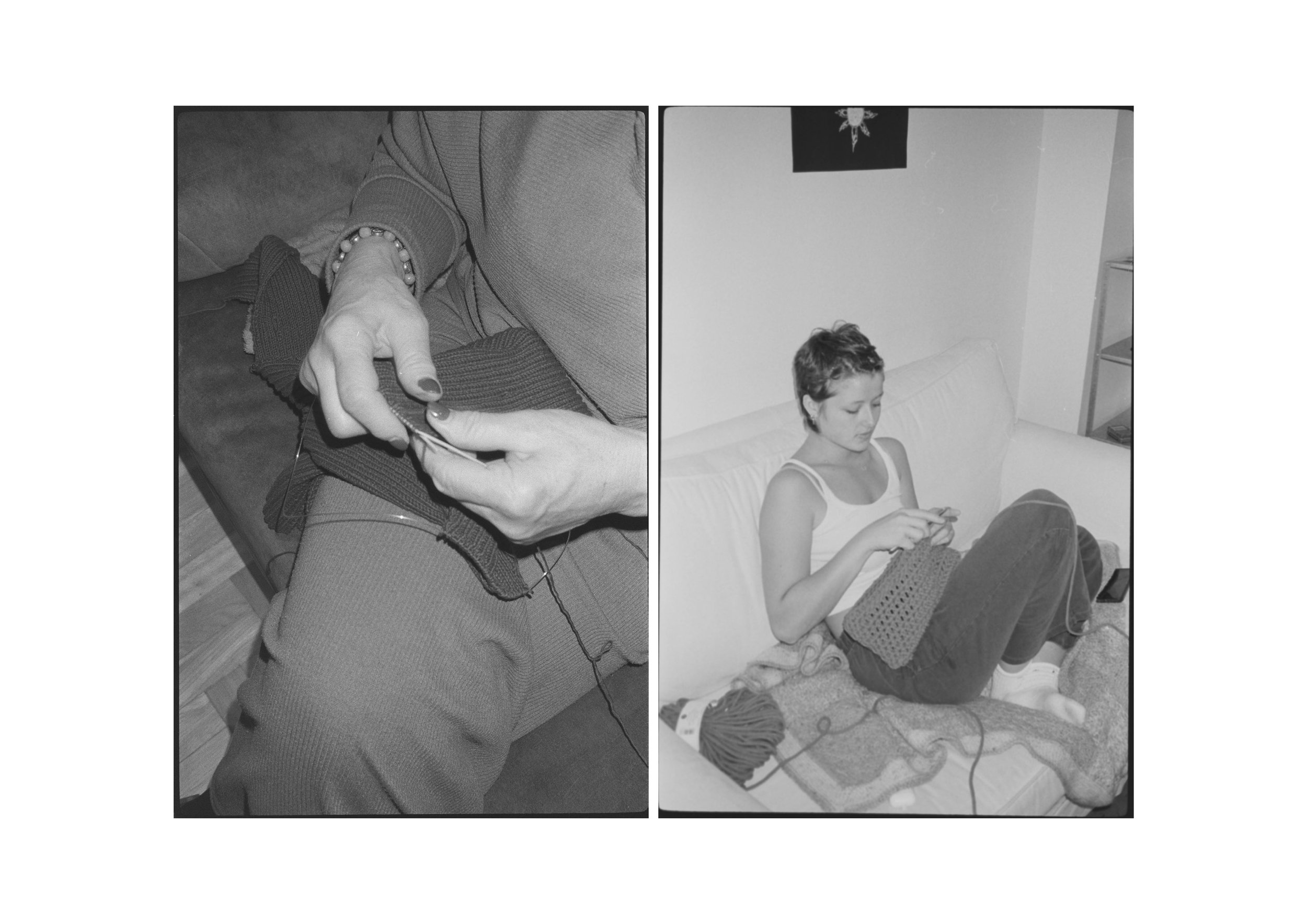

Her final project titled "Burda: Sewing Patterns.” showcases a curated collection of poetic portraits, centring on young women. It skilfully blurs the boundaries between archival and contemporary imagery and successfully captures the essence of garments passed down from generations. Each image resonates with a blend of poetic beauty and unfiltered authenticity. It feels as though each girl portrayed, became a conduit, a thread connecting the past and present in manifestation of stories and experiences of her female ancestors.

Having grown up as one of ten children in a bustling and vibrant household, Anna reflects on her childhood with a mixture of nostalgia and intensity. While delving into research for the project, she came to realise that she possessed just a few photographs of herself as a child. She shares: “We always operated as a group of siblings, and my parents lacked the necessary resources and time to capture little moments of me - being the eighth child in line. Though it can be a bit disheartening at times, I now concentrate on generating my own photo archive through my personal photography.”

Wardrobes are intimate archives holding profound value as repositories of personal narratives. They are custodians of memories and lived experiences, and their examination can reveal a wealth of information about one’s character. Anna recognises even greater potential of such wardrobe-archives. According to her, just as they bridge the past and present, they have the power to reconnect individuals, communities, and families. Researching through the notions of archives encouraged Anna to raise further questions about the role of heritage in shaping one's identity beyond the past.

How can existing archives be harnessed to construct new, modern perspectives? And raised some personal thoughts such as whether handicrafts can be a bridge between hers and her mom’s generation? Can crafts and handmade fashion evoke compassion and understanding in often troubled mother-daughter relationship?

Initiating a dialogue on Instagram, Anna raised an open call on Instagram seeking Polish girls happy to share stories related to their mothers and grandmothers closets. The response was overwhelmingly positive, with several girls eagerly sharing pictures of their cherished garments alongside corresponding reference photos from the past. Meeting with the girls in Warsaw, Anna engaged in open discussions and worked collaboratively to curate outfits for each photo shoot. Each girl would later wear the selected clothes and pose for photographs. This experience compelled Anna to reflect deeper on the ethics of photography and the politics of the gaze - topics she studied throughout her dissertation.

Having worked on commercial photoshoots and observing the dynamics of how image is created in fashion industry and film, Anna had a chance to observe the complexity of the power play between the photographer and the subject. “Some projects I assisted in were more focused on aesthetic rather than documentary”. Disliking the objectification of individuals very often present in fashion, she expressed her discomfort, noting, "I could sense that capturing someone's image was akin to a form of 'theft' for me." Analysing politics that shape the act of looking helped her develop a very own approach in her work. Anna sought to embrace the female gaze - representing multidimensional characters putting focus on complexity of personality traits, spectrum of emotions and behaviours that each character brings to the story. “The ‘gaze’ always held much political power, especially in film and photography. Gazing is about the property, about owning something. I, however, want to believe that the female gaze encourages representing characters on the screen dimensionally, stemming away from the objectification of anybody.” says Anna.

Within the realm of photography, numerous elements possess the potential to differentiate male and female perspectives. The one who determines and selects the particular fleeting second to be forever immortalised in the photograph holds enormous power over final image and messaging embedded within it.

“Reflecting on the power dynamics in portraiture (…) I invited my sitters to take a more active role in the process - each of the photographs in Burda is, in fact, an auto portrait each girl took of themselves, by using the shutter release cable.” This intentional shift empowered the sitters to take ownership of their representation. During the photoshoot Anna was responsible for choosing the frame, and all the other adjustments, but the final decision to fire the shutter was left to the girls. “Later they told me how thought-provoking this was for them, inviting them to be more present and intentional about the metaphorical meaning of the project. Through this change of dynamics from active-passive to active-active, I achieved what I never imagined I could do with my practice - create a collaborative, nourishing space for myself and the people I photograph.(…) I wish to establish mutual understanding and trusting relationships with the people I take pictures of. It’s almost like I strive for a perfect balance between us, which is hard to achieve with camera involved.”

Deciding to include herself in the photographs was not what she initially intended to do. She saw importance however to put herself in the shoes of her models. “Self-portraiture has been a part of my life since early childhood, only through the culture of selfies and social media. After examining the work of other artists, the way I view my image changed utterly.” She recalls looking at British photographer Jo Spence’s work as big influence on self-portraiture perception. Anna recalls how it was through her work that she recognised photography as therapeutic tool in a woman’s life and the power of self-portraiture to regain her own idea of a “look”.

Photographing herself wearing her mother's garments was a fascinating process of unravelling her mother's past. Anna recognised clothes as reflection of her mum’s attitude towards her physical presence. “My mum always paid attention to her arms, trying to hide them, finding them too ‘masculine’. Hence the wide sleeves or sleeveless tops. She never wore short dresses or trousers, always ensuring her varicose veins and tired legs were covered under long skirts and wide pants. (…) The clothes also told the stories about her ten pregnancies, each different from the other, asking for looser pieces and more natural materials.”

Throughout their conversation, they explored trends from the past recalling memories embedded within each piece of clothing. Each look was collaboratively selected with her mother, what made final outcome even more embedded with meaning. “We even ventured to her previous home located in the suburbs of Warsaw to see if we could uncover any hidden treasures in the attic. Unfortunately, we discovered that most of the boxes had been damaged by mice over the course of the past 30 years.” recalls Anna.

Willing to better understand and explore the political and social fabric of the communist era as well as the lived realities of previous generations she turned to archives as contextual study to inform her research. “I am not from a generation which remembers the communist time first hand, but my older siblings do. My research process involved a lot of conversations and looking at archival images from that period.. Obviously Tadeusz Rolke and Chris Neadenthal had significant influence on my work.” Photography of Rineke Dijkstra influenced her framing process : “I believe that how central the subjects are in all her photographs draws more attention to the detail and rawness of the person being photographed.” In her set design, Anna drew inspiration from the furniture and interiors that were characteristic of the communist era. These elements evoke a sense of familiarity for many Poles, connecting them to a past which still lingers in numerous Polish interiors.

The rich tapestry of inspiration found within Eastern Europe has brought fulfilment to Anna as she came closer to the topics and aesthetics of her own country during the course of the project. She articulates her longing for a greater infusion of untapped Eastern European influences in the fashion image globally: "Eastern Europe has to much to offer aesthetically. I would love to see it permeating the fashion world more” she says.

Undoubtedly, significant and thought-provoking theme in Anna's project is also the enduring lifespan of clothing aimed at challenging the throwaway culture of fast fashion dominating the industry today. Through her work, she hopes to inspire people to embrace sustainable fashion consumption, showing it not as a constraint but rather a chance to make our self expression bold and unique. Burda project prompts us to critically reflect over our own closets. What is the lasting value of our possessions? What stories will our clothes hold for generations to come?

All images courtesy of Anna Jankiewicz

Words by Paulina Czajor